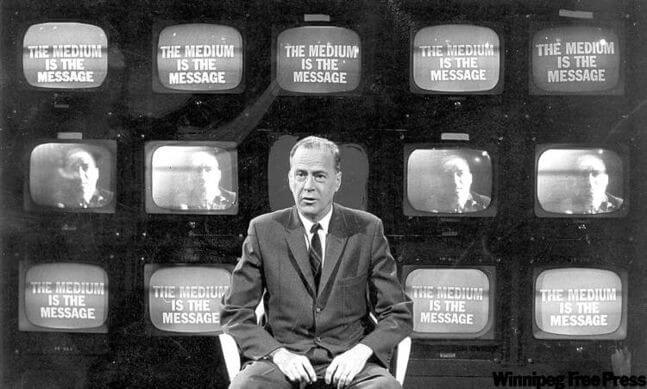

As we hit a wall the 9-month mark of the Zoomification of the classroom, I have been reflecting on Marshall McLuhan’s prescient declaration: ‘the medium is the message.’*

Writing in the sixties, McLuhan was concerned primarily with the visual broadcast (one-way) media of film and television. That said, his insights about the profound influence of form/format (even more so than the ‘content’ of communications) are more relevant than ever in the internet age.

At its worst, the Zoom classroom can feel like ‘School TV.’ Still in their pajamas–and sometimes still in bed–students tune their receivers (camera? off; mic? off) and passively bask in a faint educational glow.

This is a frustrating and stymying dynamic for educators. During a December CIE Friday Connect, folks commiserated about the challenge of reaching students through the heavy black curtain of a switched-off feed. There are good reasons (privacy, internet bandwidth, visual distractions, student anxiety or discomfort with broadcasting the surroundings they are Zooming from) behind not mandating video participation, some of them enforced by law. That said, the lack of such a mandate can quickly normalize a sense among students that Zoom learning amounts to passive consumption of ‘content.’

As an institution committed to fostering and building the skills required for lifelong learning, one of our aspirations should be to help students recognize and claim their own agency as drivers and shapers of their own education. To invite them to see themselves as creators of the classroom experience rather than passive consumers of course material.

For many of them, claiming that agency is an unfamiliar and risky proposition in the best of circumstances–and the Zoom ‘classroom’ is hardly the best of circumstances. So a question I’ve been mulling over is how we can set the tone for this kind of agency and active participation, despite the technical and social barriers involved in Zoom learning.

In the information literacy sessions I’ve taught over the past year, many instructors have used my ‘guest’ status as leverage to implore students to turn on cameras or make more active use of chat. But what if from day one, we took an opportunity to acknowledge that while the remote teaching and learning environment is less than ideal for all of us, compelling conversations and meaningful learning are still possible if we agree to bring our full selves to class as much and as often as we are able?

Can the syllabus (reinforced by first-day-of-class introductions) do some of this work, either in how it defines class participation or through a more general statement of teaching philosophy? How might students respond to an explicit acknowledgement that much of the learning value of a course is created by students themselves, both individually and in their interactions with each other and the instructor?

I’m sure our students have all had learning experiences that demonstrate that who is in the room and how they engage can have a huge influence on everyone’s learning, for good and ill. I’m sure they’ve also been encouraged in various ways to take responsibility for their own learning. Our Zoom moment offers a new context in which to consider what we all (students and teachers) bring to the experience of a course, and to make a shared commitment to do what’s in our power to transcend the limitations of a strange medium.

Of course, there will be students who don’t engage with this idea, but others might. And for those who do, a greater sense of their own agency as learners is a gift they can take with them as they continue their education, whether the next NMC class, a four-year degree, professional learning or pursuing personal interests.

*Or ‘the massage,’ – a printing error McLuhan reportedly liked so much that he kept it

Powerful and timely, as I am struggling how to address this for next week! Thank you Nicco!