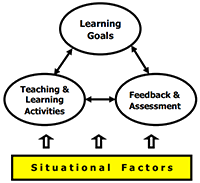

A few years ago, I attended weekend seminar “Designing Courses for More Significant Learning” – a prior version of NMC’s August professional development program. I used Dee Fink’s approach twice in major course designs, and I’ve been pleased with the results. Foundational aspect “Situational Factors” is a topic worthy of further reflection.

A few years ago, I attended weekend seminar “Designing Courses for More Significant Learning” – a prior version of NMC’s August professional development program. I used Dee Fink’s approach twice in major course designs, and I’ve been pleased with the results. Foundational aspect “Situational Factors” is a topic worthy of further reflection.

Two of the five aspects of Situational Factors are fairly static. Change occurs quite slowly in “Nature of the Subject” and “Characteristics of the Teacher.” We bring expertise to the first (and we usually keep in touch with our various fields of interest); honest reflections (when/if we’re willing) bring clarity to the other.

The other three aspects are more fluid.

External expectations are considered in “General Context of the Learning Situation.” NMC Scans help us understand regional, national, and global issues, and discipline advisory groups add local perspective.

We consider “Specific Context of the Teaching/Learning Situation” in gatherings, meetings, memos, and professional development activities. We talk of class size, delivery options, and learning environment changes (such as flipped classes). I spent quite a bit of my course design energy contemplating and working to optimize the learning environment.

Over coffee we sometimes talk of “Characteristics of the Learners.” Some courses (especially in Social Sciences) and some PDD activities address this as we consider the difficult, sometimes overwhelming circumstances facing some of our students. However, we tend to gloss over the majority of our students’ backgrounds. How intentionally and clearly do we contemplate the life situations of the rest of our learners (e.g., working, family, professional goals)? We often test prior knowledge, but do we understand experiences and feelings about our topics that students bring to our courses? Do we know students’ learning goals or class expectations?

Learner characteristics appear to evolve as our community and society adapt to changes political, economic, and social. In CIT, for example, recent students (compared with prior students) arrive with greater understanding of technology’s usage but less understanding of, and perhaps less curiosity about, how technology works.

Student collaboration has become more accepted and expected, and individual work (especially in any significant quantity) now appears distasteful. Students connect well with class lessons that are directly and currently applicable, but many show less willingness to work on projects that will not be relevant until the next step of their education or career.

Surprisingly, an eBook that worked great one semester and fine for another one or two was too difficult for following years’ students: average student age and reading ability decreased. A decade ago, 40% of my teaching was scheduled in evening hours, but the majority of those sections were replaced as we saw numbers of working adult students decline. Online and hybrid offerings ebb and flow in their effectiveness.

Considering all the change we see in our learners, we should intentionally revisit our lesson plans, our activities, our assignments, and pretty much all other aspects of our courses now and then. To really help our learners learn, we need to understand who they are – the ones with us currently, not just others we met a few years ago.

References: Personal notes and pre-workshop reading assignment on “Designing Courses for More Significant Learning” by L. Dee Fink