TL;DR (too long; didn’t read) – New research shows that the college classroom is a high-impact context for developing students’ attitudes, habits and literacy when it comes to engaging with news media, and that college faculty are uniquely positioned to influence students’ information-gathering behavior in both academic and personal contexts. If you are interested in exploring ways to use journalism and current events both to help students synthesize and apply course material and develop news literacy and civic engagement, I’d love to chat with you about it! (npandolfi@nmc.edu)

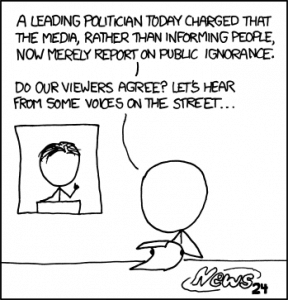

“The news is all biased. None of it can be trusted.” — I. M. A. Student

I’ve been teaching information literacy skills and research strategies at NMC for just two short years. Yet in that brief time, I have quickly lost count of how many times I’ve heard some version of this sentiment voiced by an NMC student.

That students have adopted a categorical mistrust of journalism as they stew in a cultural climate of stark polarization, ‘alternative facts,’ and a splintered, choose-your-own-adventure media landscape shouldn’t surprise us. But that doesn’t make it any less disturbing.

In my first few months at NMC, I was struck by something Kristen Salathiel said as we planned an information literacy instruction session for one of her English classes. She said that over the course of her years teaching at NMC, she has observed a striking shift in her students’ attitudes toward the news: from naive credulity (if it got published it must be true) to cynical dismissal (all news is irredeemably biased).

The most important, and most interesting, part of my job is trying to figure out better ways to help students develop mental models to navigate, evaluate and use information well — mental models that span the various contexts of their life. And I can say without hesitation, that given the choice between:

A) Guiding students from a position of naïve credulity to one of disciplined skepticism; and

B) Guiding students from a place of undisciplined skepticism to one of disciplined credulity;

I would choose the former every time. As anyone who has suffered a breach of trust knows, rebuilding it is much harder than establishing it in the first place. Unfortunately, that’s not the hand we’ve been dealt. Instead, every day brings more evidence that we are living through an epistemic crisis about how we know things to be true, and how we use that knowledge to construct a shared reality.

So what can we do about it?

A recent study surveyed over 5,800 undergraduate students from 11 different colleges and universities about their attitudes and behaviors related to finding, reading and discussing the news. One of the most striking findings was the significant role classroom discussions and faculty modeling of engagement with the news played in influencing students’ news habits. The authors found that faculty were uniquely situated to model and foster news literacy and news-gathering behavior for both personal and academic purposes.

They also found that students were much more likely to have opportunities for classroom engagement with news and current events in the humanities, arts, and social sciences (77%) than in STEM fields (48%). Such a disparity suggests a tendency to view news literacy as squarely within the purview of the humanities and social sciences. However, as the authors note,

The authors also cite prior literature that demonstrates the valuable role current events and news can play across disciplines in helping students deepen and apply their understanding of core disciplinary material.

As educators, we have an opportunity and a responsibility to equip our students to navigate an ever more complex information landscape that will shape every facet of their lives in ways both obvious and nuanced. Integrating connections to journalism and current events into your course can be done in small, simple ways to great effect. Far from taking away from student learning of ‘core’ curriculum, it can enhance it. What’s more, you don’t have to do it alone! Drop me a line to start a conversation about how the library can support you in this work. We are your committed collaborators and co-conspirators.

Well said, Nicco! Honestly, I think teachers are partly to blame. There was a big emphasis on media bias a few years back. Students were taught to look for media bias without being taught the fundamental characteristics of journalism and other types of media. For example, a lot of students (and teachers) underestimate commercial bias and overestimate political bias because they don’t understand media as a commercial enterprise.

I am trying to focus on teaching students to identify the rhetorical situation of a text — particularly audience, purpose, and genre. Once they know what a text is or is presenting itself as, then they can better figure out whether it is credible and useful.